Last time (here), I started a rather stupidly ambitious plan to look at Alberta’s liquor system and offer something of an analysis – at the risk of losing readers either through boredom or political disagreeement. But mostly it has just turned out to be a much bigger job than I expected (I am feeling I needed to make someone pay me to publish a book on this stuff rather than toss it out for free on my website).

I started by looking at the retail end of things, and its effect on consumers and craft brewers. In this post I want to look at the production end, as that is a key part of the puzzle. I admit on this topic I am on less solid ground. Even though I have done my research, I have not lived the rules, like our small brewers have. So, I may be missing some nuance or complication that profoundly affects their life.

In contrast to Alberta’s liquor retail laws, which are all about “free enterprise” (except for the private monopoly part), the province’s rules for beer producers are actually more restrictive than most jurisdictions. Alberta sets a minimum capacity at start-up of 5,000 hectolitres (HL – a hectolitre is 100 litres), requires all tanks to be at least 10 HL in size, and requires a production capacity (even in the first year) of 2,600 HL. Brewpubs have different rules (requiring a minimum of 520 HL and a maximum of 10,000 HL). That is a lot of numbers that may not make a lot of sense. But we know a few things from them. First, any kind of attempt to create a nano-brewery or boutique brewery is out of the question. To start you need to have a substantial system. 5000 HL is quite small in the beer world, but it does move you into the HUNDREDS of thousands, rather than tens of thousands of initial investment. This, alone, is a problem as it shuts out what can be the most innovative and local of craft brewers.

Breweries that produce less than 20,000 Hl get a break on provincial taxes, paying about 1/5 what the big boys pay. Between 20,000 and 40,000 they pay about half. It is not the largest possible break, especially given the onerous start-up rules, but it is not insignificant. It helps in a noticeable way in keeping the price of craft beer lower. However, there are two issues with this system. First the rate is not graduated, meaning that when a brewer hits 20,001 or 40,001 Hl the cost of their ENTIRE production jumps to the higher tax rate. That makes for a very expensive extra litre. This creates the situation where small brewers can’t really afford to grow bigger. And as long as they stay small, they will never capture more than a small sliver of the market. It is an unintended consequence of the tax policy. Of course, an ambitious brewer could plan for that jump, but that takes a fair bit of capital and as we all know, capital is usually in short supply in craft breweries.

The second problem is that the 20,000 to 40,000 rate is also offered to any brewery that imports into Alberta. This is a very divisive issue. On the one hand, it gives an advantage to breweries who brew outside Alberta (often cheaper) who want access to our market. The reason it advantages them is that they don’t have to deal with Alberta’s other restrictive rules, yet they get the price break.

That said, I have also been told in no uncertain terms that the “transitional rate” (which is what the middle rate is called) and its application to imported beer is a life preserver to many small craft breweries trying to find enough market to make a profit. Paddock Wood, Yukon, DDC, Half Pints and many other amazing breweries breath a sigh of relief knowing that they are eligible for the cut rate. Without it, their beer would be about $1.20 more a six pack if they had to pay the full rate. While that doesn’t sound like much, it can make a large difference among the price-conscious beer consumer. I know that I couldn’t care less about another buck or so to get great beer, but I also know I am in the minority on this front.

This is one of the most complex issues in Alberta’s beer system. What should we prioritize? Locally produced beer? Or small brewery beer from around the world? On the surface, I would say both, but it is quickly becoming clear to me that we can’t have both. One undermines the other. It is a tough spot.

One of the things that creates this dilemma is that Alberta has entirely open borders, as mentioned in the first part of this series. However, every other province is more restrictive, meaning it is easy for an Ontario brewery to enter Alberta, but good luck to an Alberta brewery getting into Ontario. This is not necessarily Alberta’s fault, but it remains a real problem for the men and women in Alberta trying to sell beer. I am not advocating, necessarily, for Alberta to close its borders, but we need to acknowledge the uneven playing field that Alberta’s privatization created. It has constructed a problem for Alberta’s brewers that didn’t exist before.

The final issue related to the producer side of things is that the AGLC doesn’t understand beer. No one working for them has ever been a part of the beer industry, and they don’t really get the struggles of running a small brewery. That is why they don’t enforce their anti-inducement rules, and why they throw out knee-jerk rules like last year’s short-lived ban on beer over 11.9% alcohol. A body that had some insight into the beer industry might find a way to construct policies that supported craft breweries, rather than make their life harder.

Alberta is not the easiest province to be a small brewer. I have done research in a number of provinces, and many actively try to support their local brewers (to greater or lesser effect). Nova Scotia aggressively promotes their brewers, giving them more shelf space than their sales might normally justify. B.C. guarantees regional distribution in government stores (although this system is imperfect). Manitoba has built a good relationship with their small brewers. Alberta, on the other hand, washes their hands of the struggles of craft brewers, claiming their mandate is not to promote local producers. And as a result, the advantage goes to the big players.

The set of issues related to producers is, on the surface, disconnected to consumer issues. However, you cannot analyze the parts of the system in isolation. It all fits together, meaning we need to evaluate it as a whole.

I know I promised some of my ideas for how to improve the system. I can do that, but this post has gone on too long, meaning I need to break my promise of doing this in two parts. The third part will need to focus on my ideas for how to make Alberta a better beer place. Thanks for your patience.

June 20, 2012 at 11:44 PM

I agree with Part 2 (disagree with Part 1). The idea of minimum production limits is just silly, merely a way to exclude people from trying to start things up. SK has a similar idea at a lower level, and applies it to brewpubs as well (200HL in cities, 50HL in small towns). They claim they do not want people to fail, so they set reasonable targets. I say, if you think you can make money producing even 5HL a year, go for it. Why should government care about the success or failure of entrepreneurial ideas.

I recall back in 2007 ON offered a reduction in mark-ups to craft breweries because they had such a great impact on local employment. Ironically the very same month SK increased mark-ups on craft beer by 20 cents/L.

June 21, 2012 at 12:42 AM

Next time you go into a local liquor store – don’t be surprised to see a Coke or Pepsi cooler filled with juices and mixers…

Tied Houses are legal in Alberta – as long as you have a brew-pub license. The quirk is if you have a tied house (brew pub) you cannot sell the beer to another independent licensee or brew under contract for another firm.

According to the AGLC – if you are deemed a micro brewer – inducements like the provision of a $500 kegerator to ensure properly served draft beer or volume incentives for the best clients are illegal. However – $500 tickets to NHL games (the retail value equivalent of 2 x 1/2 barrel kegs)used to induce beer sales for special “events” is allowed.

Inducements are a fact of life in many circles – including when hotels and schools accept a contract from Coke or Pepsi (free use of a cooler) as long as the client stocks their beverage products.

If the supply of soda guns, cold plates and CO2 lines were deemed illegal – small bars would be relying on bottled and canned soda drinks more often as they would likely not be willing to invest thousands of dollars for the equipment necessary for a post-mix soda dispenser.

The big brewers play by a similar code of conduct in Alberta – the question we need to ask is why is it deemed LEGAL and a fact of life for a liquor store or bar owner to rely on an inducement from a soda pop supplier, for access to a freely delivered “loaner” cooler or use of a “soda gun” – but completely ILLEGAL for a craft brewer to supply more than a tap handle?

On a whole – the inducement regulations – if enforced by AGLC – provide for the possibility of a more even playing field – if they are enforced. If not – the threat of a $200,000 fine to a small brewer is far more significant than to a billion dollar firm. Thus, many of these antiquated laws provide a greater impediment to the small 5000 HL brewer ($40/HL) than a conglomerate (pennies per HL).

One should question the following statement:

7.2.1 A liquor supplier is prohibited from directing any promotional activity or items to a licensee that could directly benefit the licensee or its staff, and a licensee may not request or accept any such inducements.

In Ontario – the Beer Store charges hundreds of dollars per store “stocking fees”…these stores are controlled by Molson Coors and AB-Inbev.

I find it funny that while in Ontario – Beer Stores can charge a “slotting fee” to guarantee shelf position – but this form of commerce in Alberta is deemed “Illegal”. Thus, this makes the export of Alberta beer into Ontario a very expensive proposition if cold beer space is required. Not only are brewers of Alberta facing extremely expensive temperature controlled shipments into Ontario – even before the beer can be shelved – additonal fees must be paid to a group that is controlled by the largest brewers based in Europe and USA.

If there is no documented and publicly released inforcement of the convoluted policies surrounding the sale of a natural product like beer – should they not be struck from the books?

In some states – inducements are set at an annual level of $50.00 per account. Bars come to accept that the provision of glassware comes at a cost from the brewer. The brewer is obliged to charge market rates for glassware and signs. If Alberta had similar rules that were enforced a craft beer lover could buy a branded glass from a liquor store for $3 and the retail liquor store could make money on that item…why not? Did I fail to mention that the sale of Branded galssware is illegal in Alberta if sold by liquor stores?

The US brewers who I speak to seem to all agree that their respective states do a good job of enforcing their “inducement” laws – perhaps this is why you see far more brewers in USA than Alberta per capita?

August 23, 2012 at 3:24 PM

Where did you get this information?

AGLC requires a mere 10hl capacity for a brew pub, not 520hl…

August 23, 2012 at 9:29 PM

Mike,

I got this information from the AGLC. I was referring to annual production capacity, not brewhouse capacity.

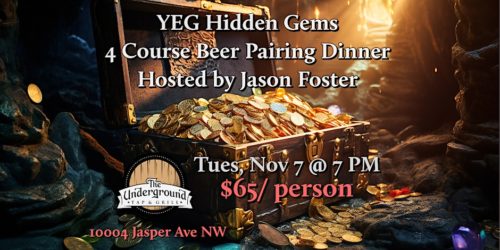

Jason